The rise of Impressionism can be seen in part as a response by artists to the newly established medium of photography. In the same way that Japonisme focused on everyday life, photography also influenced the Impressionists’ interest in capturing a ‘snapshot’ of ordinary people doing everyday things.

Still Life Orchids & Horses by João Carlos

The taking of fixed or still images provided a new medium with which to capture reality and changed the way people in general, and artists, in particular, saw the world and created new artistic opportunities.

Learning from the science of photography, artists developed a range of new painting techniques. And, rather than compete with the ability of the photograph to record ‘ a moment of truth’ the Impressionists, such as Monet, felt free to represent what they saw in an entirely different way – focusing more on light, color, and movement in a way that was not possible with photography. Over time, these subjective observations became much more widely accepted as works of art, although initially they were thought to be ‘sketchy’ or ‘unfinished’.

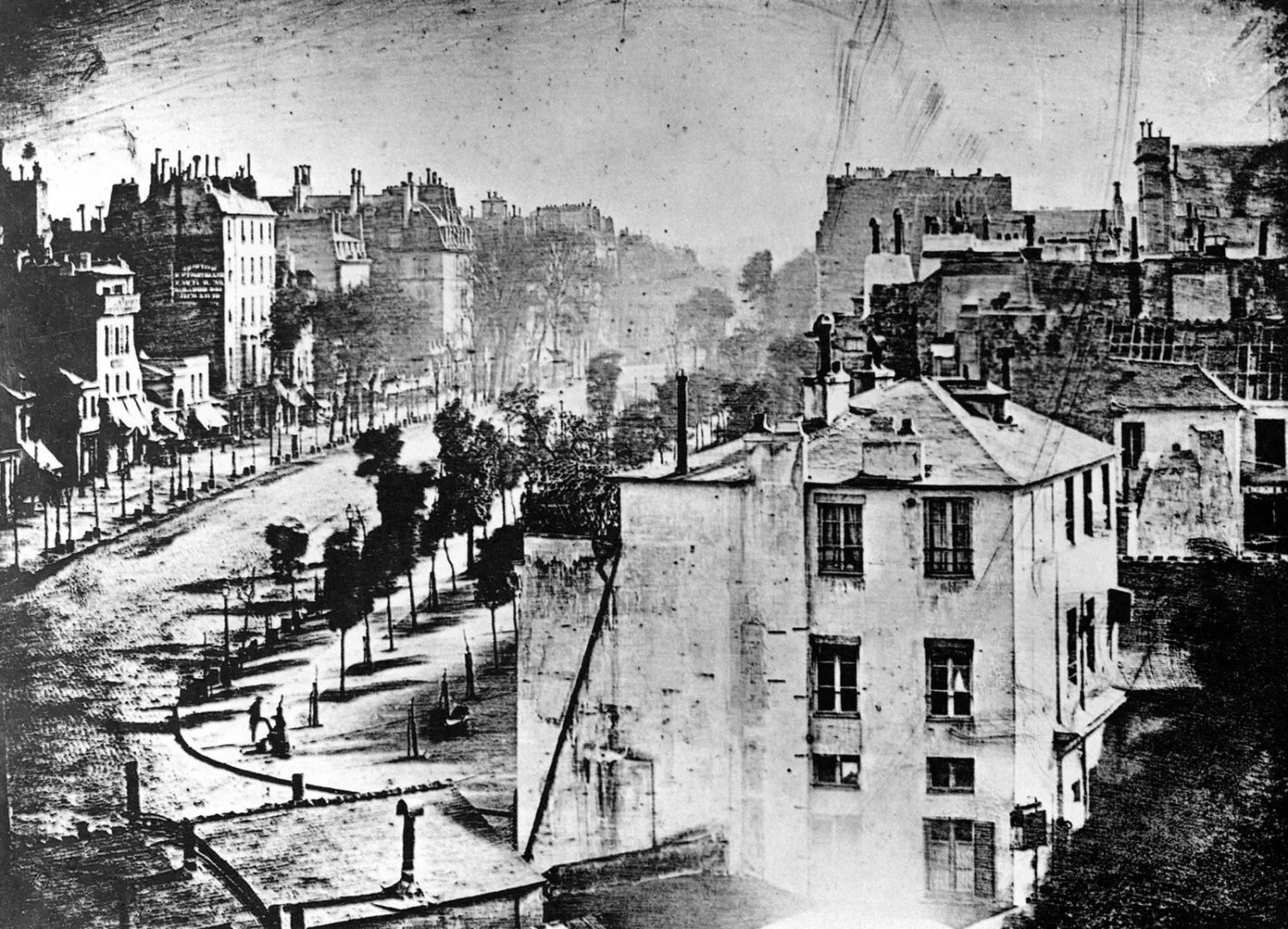

In 1839, a new means of visual representation was announced to a startled world – photography. While photographers themselves spent the ensuing decades experimenting with techniques and debating the nature of this new invention, its impact on modern society proved immense.

View of the Boulevard du Temple, Paris, daguerreotype by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, c. 1838.

Today, it might be difficult to appreciate how revolutionary and challenging photography was, but the art world quickly took notice when it first stepped into the scene. What started as a competition soon became an alliance of vision that changed the way we see it forever. It radically changed how artists, particularly the Impressionist painters, looked at the world and depicted reality.

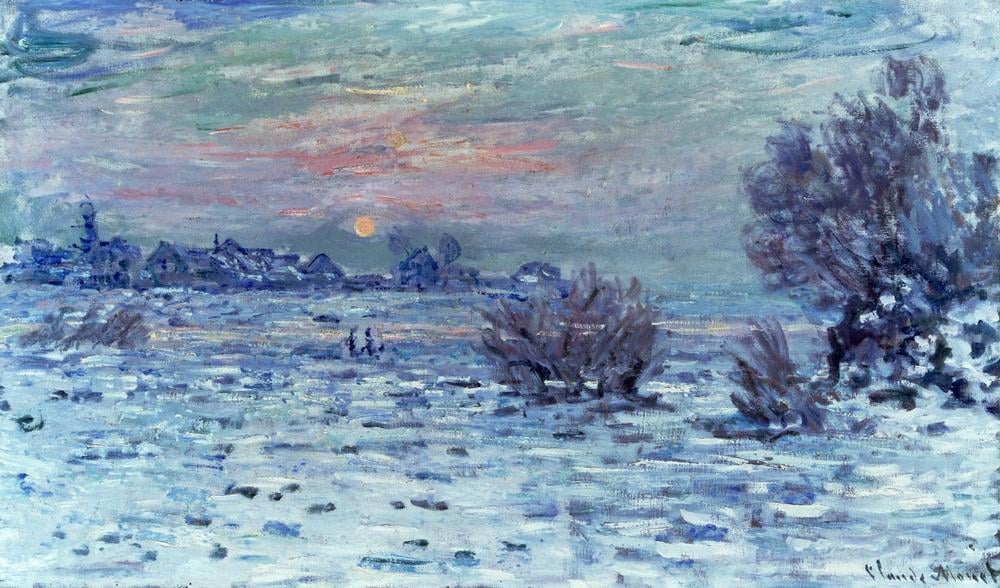

Ice & Light Illuminate a Pivotal Landscape by Monet

When Claude Monet painted La seine à lavacourt, débâcle in 1880, he wasn’t just capturing a key moment in France’s history – he was also beginning his first real series, an approach he’d famously continue over the remainder of his career. That winter, the Seine froze over – the result of France experiencing one of the worst freezes in the country’s history. On the morning of January 5th, when the ice finally began to break, Monet ran to the river and began painting en Plein air, intent to capture the sublime moment. Over 20 canvases, Monet recorded minute changes to the scene: how the light reflects against the breaking ice, the movement of the river, and the bitter freeze crystallizing the landscape. Ahead of the work’s appearance in the New York’s Impressionist & Modern Art Day Sale this May, join specialist Scott Niichel as he discusses the importance of La seine à lavacourt, débâcle in the evolution of Monet’s career.

When Claude Monet painted La seine à lavacourt, débâcle in 1880, he wasn’t just capturing a key moment in France’s history – he was also beginning his first real series, an approach he’d famously continue over the remainder of his career. That winter, the Seine froze over – the result of France experiencing one of the worst freezes in the country’s history. On the morning of January 5th, when the ice finally began to break, Monet ran to the river and began painting en Plein air, intent to capture the sublime moment. Over 20 canvases, Monet recorded minute changes to the scene: how the light reflects against the breaking ice, the movement of the river, and the bitter freeze crystallizing the landscape. Ahead of the work’s appearance in the New York’s Impressionist & Modern Art Day Sale this May, join specialist Scott Niichel as he discusses the importance of La seine à lavacourt, débâcle in the evolution of Monet’s career.

Early Photography

In 1839, Daguerre’s disclosure of the secret process he used to record an image onto a silvered sheet of copper, which was the first workable and permanent method to achieve this (known as the Daguerreotype), led to the invention of the photograph, which was to become one of the most popular inventions of the century.

A New Way of Looking At the World

Following the appearance of the first daguerreotypes in the late 1830s and the subsequent discovery of techniques for making photographic prints on paper, a very close relationship was established between photography and painting. The artificial eye of the camera of photographers such as Gustave Le Gray, Eugène Cuvelier, Henri Le Secq, Olympe Aguado, Charles Marville and Félix Nadar spurred Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas and the young painters of Impressionism Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Alfred Sisley, Claude Monet, Marie Bracquemond, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot and Gustave Caillebotte to devise a new way of looking at the world.

As photography evolved from a mere mechanical means of reproducing reality to gaining artistic credibility, it allowed painters a closer examination of light and asymmetrical, cropped spaces, as well as an exploration of spontaneity and visual ambiguity. This relationship was mutual, as the medium of photography became concerned with the materiality of their images and sought methods for making their photographs less precise and more painterly. Painters of Impressionism were keenly aware of the transient nature of reality and, for them, photography seemed to mark a symbolic victory of man over temporality and triggered a revolutionary transformation in their depictions.

By 1849, some 100,000 Parisians* were having their pictures taken every year. (Interestingly, in the same way, we use Photoshop today, customers often requested that their photograph be re-touched to hide perceived faults, or to add color.)

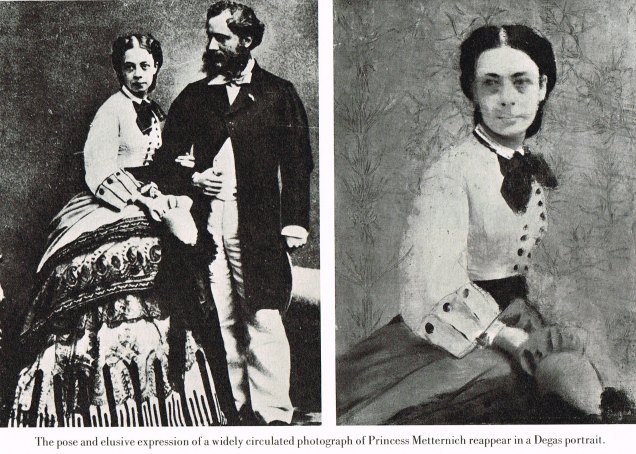

Daguerreotypes were unique and non-replicable, but with the introduction of the carte de visite (visiting or calling card) in the 1850s photographic images could be produced cheaply and easily distributed. Cartes de visite were prints, usually, albumen, affixed to a card measuring about 6 x 10cm. This standard format was patented by a French photographer, Andre Adolphe Disderi, in 1854. Through the use of a sliding plate holder and a camera with four lenses, eight negatives could be taken on a single 8″ x 10″ glass plate, which allowed eight prints to be made every time the negative was printed.

Cartes de visite were most popular from the 1860s to the 1890s, largely coinciding with Impressionism.

Influence on artists

Some artists found they lost commissions to paint small intricate portraits in favor of people preferring to have studio photographs taken. However, for others, it became an inspiration for new ways of not only composing their artworks but also painting using more experimental techniques.

Photographs (as they do today) assisted in the portraiture painting process. Many artists found that they could do away with tedious sittings of models and instead use shorter sittings and photographs to paint portraits. Portable cameras could also be taken outdoors to record landscapes – enabling the painting process to be completed in the studio.

In the early stages of camera development, long exposures with a camera were required to capture the image, which created ‘shutter-drag’, allowing for beautiful fluid movement and gracefully blurred selections. Some artists, such as Degas, sought to recreate this effect to soften the overall painting.

One of the most famous photographers from the mid-1800s was Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) who established the most fashionable portrait studio in Paris – it was here that the Impressionists held their first exhibition in 1874.

As the medium developed, photographers like Eadweard Muybridge experimented with the camera’s stilled or stopped movement.

Stopping action was a fascinating new concept. Before photographic stop-action, it was difficult to capture a muscle in a state of tension, or the gait of a horse in mid-step, for example.

Edgar Degas

Edgar Degas was one Impressionist who was so intrigued with this new ability to capture a moment in time that he also pursued photography as a creative outlet. There are a number of examples of how he used his knowledge of photography in his art, which you can see in his sketches and paintings of racehorses. For example, he was amazed that Muybridge’s photos proved that a horse’s feet leave the ground in a rolling sequence, not in the “hobbyhorse” pairs that most artists favored.

In the above paintings by Degas you can also see the technique of cropping, that is selecting only part of a subject to be included in the picture plane, allowing for a more intimate connection with the viewer, as it creates the illusion that there is a larger scene, just outside of the viewer’s vision. Cropping became an important compositional technique adopted by many artists.

Photography, far from limiting the appeal of paintings, provided artists with new points of view and encouraged them to translate photographic techniques in their work, enabling them to capture everyday life with a greater sense of vitality and intimacy.

Reference

* Pierre Schneider, The World of Manet, 1832-1883, Time-Life Books, 1968

Impressionism – The influence of Photography